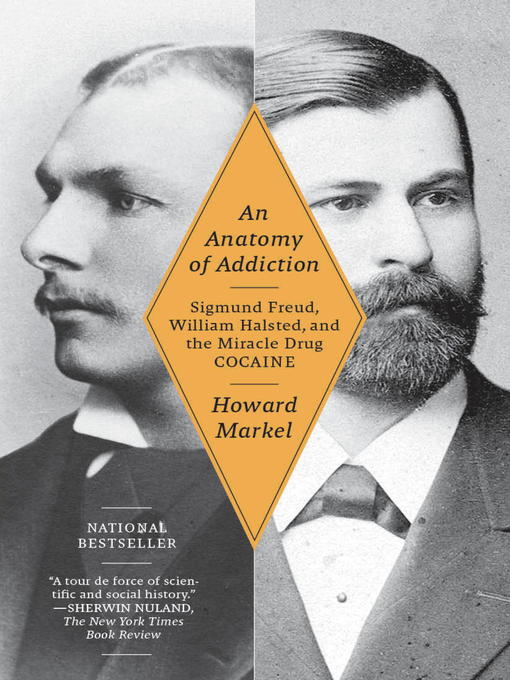

Acclaimed medical historian Howard Markel traces the careers of two brilliant young doctors—Sigmund Freud, neurologist, and William Halsted, surgeon—showing how their powerful addictions to cocaine shaped their enormous contributions to psychology and medicine.

When Freud and Halsted began their experiments with cocaine in the 1880s, neither they, nor their colleagues, had any idea of the drug's potential to dominate and endanger their lives. An Anatomy of Addiction tells the tragic and heroic story of each man, accidentally struck down in his prime by an insidious malady: tragic because of the time, relationships, and health cocaine forced each to squander; heroic in the intense battle each man waged to overcome his affliction. Markel writes of the physical and emotional damage caused by the then-heralded wonder drug, and how each man ultimately changed the world in spite of it—or because of it. One became the father of psychoanalysis; the other, of modern surgery. Here is the full story, long overlooked, told in its rich historical context.

- Available now

- New eBook additions

- New kids additions

- New teen additions

- Most popular

- Spanish Titles for Young Readers

- Try something different

- See all

- Available now

- New Audiobook Additions

- New kids additions

- New teen additions

- Most popular

- Try something different

- See all